By Sara Crouch, CRC Peace Education Intern

As I sat listening to a panel with the authors of the new book Colorizing Restorative Justice: Voicing Our Realities as part of my internship with CRC, one author, Edward Valandra, spoke about his piece “Undoing the First Harm: Settlers in Restorative Justice” which discusses his concern about white settler practitioners using Indigenous-based restorative practices, such as circle process, while failing to address the “First Harm” of the land they reside on: the genocide and forced removal of Indigenous people from their ancestral lands in the name of settler expansion. Valandra explicitly stated that as a first step to undoing this harm, practitioners should be beginning their restorative processes with an Indigenous land/territory acknowledgement to recognize the harm that continues to be done against Indigenous people and celebrate the continued resistance and existence of Indigenous people.

That call to action inspired this overview of Indigenous land acknowledgements, and how to implement them as part of restorative practices.

What is an Indigenous land acknowledgement?

An Indigenous land or territory acknowledgement is a statement made by an organization or individual that expresses their acknowledgement of the original Indigenous owners of the land they are standing on and the continued colonization of these Indigenous peoples. It is a simple yet powerful way to offer respect to and recognition of Indigenous people and their right to their ancestral land and counter the mainstream erasure of Indigenous people’s history and culture.

An acknowledgement shows support and accountability to Indigenous communities, and recognizes the long history of genocide, stolen land, and forced removal of Indigenous peoples in that country. It also reminds folks that colonization continues today, with Indigenous people still being denied their lands through illegal occupation and broken treaties. Indigenous land acknowledgments also intend to inspire ongoing support and relationship with Indigenous community members.

How?

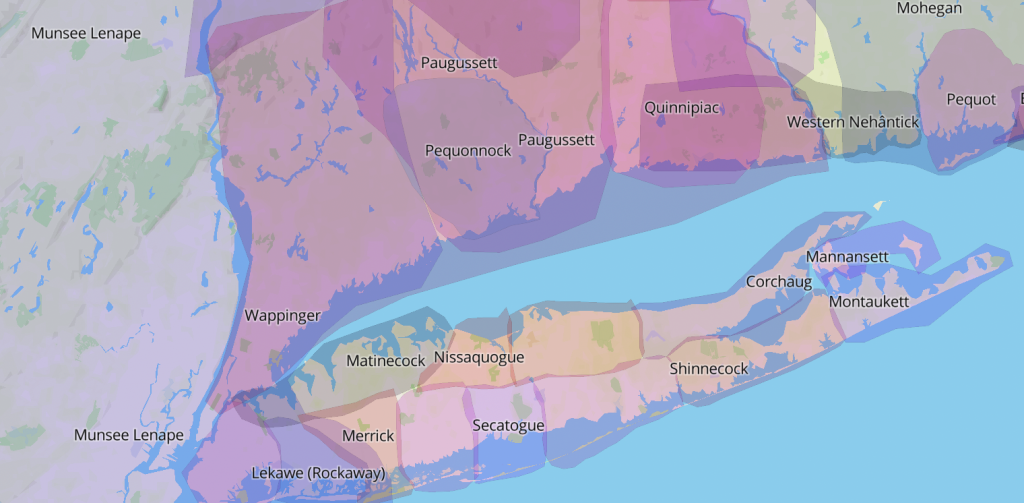

There is no one way to do an Indigenous land acknowledgment, but there is certain information that should always be included in these statements. These are the name of the Indigenous people whose ancestral land you are on, recognition of their continued ties to the land, and acknowledgment of the continued harm of Indigenous people through colonization. If possible, you should also refer to the land you are on by the name given to it by its Indigenous owners.

If you live in North America, Australia, New Zealand, Greenland, Northern Europe, or South America, you can quickly familiarize yourself with whose traditional land you are on by visiting this map.

New York University offers a simple template for institutional land acknowledgements:

We are gathered on the unceded land of the [ ] peoples. I ask you to join me in acknowledging the [ ] community, their elders both past and present, as well as future generations. [Name of institution] also acknowledges that it was founded upon exclusions and erasures of many Indigenous peoples, including those on whose land this institution is located. This acknowledgement demonstrates a commitment to beginning the process of working to dismantle the ongoing legacies of settler colonialism.

Creative Response to Conflict has been using the following land acknowledgment, adapted from one drafted by consultant Jill Sternberg:

Today we begin with a practice of respect and recognition for being a guest in someone else’s space. We acknowledge that we gather as guests on the traditional territory of the Ramapough Lenape people. This is the ancestral area of the Hackensack, Tappan, Rumachenanck, Munsee, and Ramapo clans. They are the original stewards of this land from which most were removed unjustly. We pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and future.

As we remember the stewards of this land, let us acknowledge that the restorative practices we are discussing come from them. Let us thank the people who, upon the first settler contact had lived here for at least 3,000 years and whose history with this territory is at least 7,000 years old.

Let us be mindful we are on stolen native land built up by the stolen labor of enslaved Africans. Let us thank Native Americans and African Americans for sharing their cultures and practices with us despite the havoc European settlers wreaked on their societies. Let us take time and make the effort to understand societies before European contact, and how those impacted live today. Let us be mindful of the ongoing impacts of colonization, slavery, and loss of culture. We are mindful of broken covenants and the need to make right with all of our relations. Let us commit to ending injustice and restoring balance to Mother Earth.

Circle-keepers can integrate this practice into their restorative circles by including a land acknowledgment in their opening ceremonies, as well as during the introduction phases of restorative conferences and training. This is also a time to acknowledge the Indigenous roots of restorative justice and continued Indigenous peacemaking efforts.

Guidelines

The Native Governance Center offers some general guidelines for creating an Indigenous land acknowledgement. Firstly, the organization or individual should start with self-reflection about what their motivations and intentions are for creating an Indigenous land acknowledgement. This process should be one of genuine support, not conformity.

Second, you must do your research while creating an acknowledgement. Contact your local Indigenous community members about the history of their people in the land you’re on, and ask them what you can do for them. Additionally, make sure you are referring to Indigenous folks as they would like to be addressed.

Third, don’t use sugarcoated language to describe the harm done and being done to Indigenous peoples. Use accurate language like genocide, stolen land, and forced removal to discuss these harms and bring clear attention to it and its perpetrators.

It is also crucial to use past, present, and future tenses when talking about Indigenous people in these acknowledgments. Most mainstream discourse regarding Indigenous peoples erases their present existence and resistance, thus it is essential for land acknowledgements to counter this narrative and recognize the past, present and future existence and land ownership of Indigenous peoples. Lastly, it is important Indigenous land acknowledgments are not overly grim. While these statements bring attention to harm, they are also a celebration of Indigenous people and the positivity of who they are today.

To learn more about Indigenous land acknowledgments, check out the USDAC #HonorNativeLand project and the Native Governance Center’s Guide to Indigenous Land Acknowledgements.

Sara Crouch (she/her) is a graduating Global Studies student from Long Island University Global, an experiential 4-year undergraduate degree program that has students study in over ten countries. Her research and practice revolve around grassroots peacemaking, restorative justice, and peace education. Sara served as a Peace Education Intern for CRC between February and May of 2021.

References

Felicia Garcia (Chumash), M.A. Museum Studies, New York University (2018). Guide to Indigenous land and territorial acknowledgements for cultural institutions. Built upon the important work of the Lenape Center, American Indian Community House, Rick Chavolla, Emily Johnson, the New Red Order (NRO) and the Native American and Indigenous Student Group (NAISG) at NYU.

U.S. Department of Arts and Culture. Honor native land: A guide and call to acknowledgment.

Native Land Map.

Edward C. Valandra (2020). Undoing the First Harm: Settlers in Restorative Justice. Colorizing Restorative Justice: Voicing Our Realities. Living Justice Press.

Native Governance Center. A guide to Indigenous land acknowledgment.

Morningside Center (October 8, 2020). Acknowledging and Expressing Gratitude to Indigenous Peoples.